From Wonder to Thought – A Short Journey into the Beginnings of Philosophy

When did we actually begin to truly engage with our own questions?

I’m not even sure where to start when saying: I want to understand philosophy.

There are so many names, so many systems, and all of them seem to be already deep in thought while you’re still standing outside the door. So I ask myself: where do we begin? With Kant or Nietzsche? Probably not – that would drop us right in the middle. Perhaps it’s better to go back to the very beginning, to the moment when thought first came up with the idea that one could even ask.

Maybe with the Ionians – Thales, Anaximander, Heraclitus. Names that sound as if carved in stone today, but back then they were simply people who asked questions for which no language yet existed. I imagine them standing somewhere by the sea, feeling the wind, hearing the surf, and thinking: there must be something that holds all this together. They lived in a world full of gods, yet they did not want to believe – they wanted to understand.

We have to keep in mind: back then, no one had seriously reflected on what “the world” even was. People simply took it as given. And when you know almost nothing, when hunting, sleeping, making fire, and surviving define your day, it’s only logical to begin with the simplest questions – just as we now approach philosophy: step by step, starting from the simple.

From Myth to Wonder

Before those early thinkers appeared, people explained the world through stories.

The sky was full of gods, the sea had moods, thunder spoke with the voice of Zeus. Everything had intention, everything was alive, and what was alive could rage or help. There was order in chaos – not nature, but will.

Then a different kind of storytelling emerged. With Homer, the world entered language. The Greeks began not only to tell about life but to arrange it in rhythm and image. To this day, we don’t really know who Homer was – a single poet, a generation of singers preserving his verses, or perhaps only a name standing for a shared tradition.

This poetry was not yet philosophy, but it prepared the ground.

It taught that the world can be formulated – and once you can put it into words, you can begin to ask questions.

Soon after, the Ionians appeared.

What these early natural philosophers did was revolutionary: they began to explain the world without divine intervention. Not because they were against the gods, but because they had suddenly realized that one may also ask how things happen, not only why.

They searched for causes, not stories. Instead of Zeus and Poseidon, they spoke of water, air, motion, change.

Today that sounds simple, almost obvious. But back then it was a break with everything people knew. They stood against centuries of myth – not out of defiance, but out of curiosity. Perhaps it wasn’t even a conscious rebellion, but a quiet sense of wonder that no longer accepted the old answers. And thus something began that continues to this day: the attempt to see the world with one’s own eyes.

(For the sake of further thinking, I’ll first get myself a coffee – my head is already steaming. With every line, new questions arise, and I suspect that will never stop.)

Socrates and the Courage for Truth

When you imagine how everything began, you suddenly realize that the path of philosophy was never as straight as textbooks make it seem. It wasn’t a planned ascent toward knowledge, but a groping, a wandering, a repeated losing and rediscovering. And perhaps this is exactly where Socrates belongs – as someone who did not see ignorance as weakness, but as a beginning.

While the natural philosophers tried to grasp the whole of the world, he asked: What about us?

(That always reminds me of a Michael Jackson song — funny how even ancient questions echo in pop culture.)

With Socrates, philosophy turned inward. It no longer looked only at stars, stones, and elements, but at the very thing that questions, doubts, and acts. He brought thinking back to ourselves. For what use is understanding nature if one does not understand oneself?

Sadly, Socrates’ story did not end well. As in every age, too many questions proved uncomfortable to those in power. Socrates was no enemy of democracy, but he was a provocation. He questioned everything that seemed self-evident: knowledge, virtue, power, piety. Those who faced his method soon realized how little they truly knew – and that made him dangerous, especially to those who thrived on reputation, authority, and public admiration.

One could say he was condemned not for his ideas, but for his effect.

He made people think – and thinking is dangerous when a society is tired. Athens had lost wars, old certainties had cracked, and suddenly there was this man asking every politician and priest whether he truly knew what justice was. In times of insecurity, people dislike mirrors, and Socrates held up a particularly clear one.

He could have fled – his students offered to help – but he stayed. He believed that one defends conviction not by running away from it. And so, as the story goes, he calmly drank the cup of hemlock – not as an act of martyrdom, but as the final proof of his philosophy: that reason and conscience matter more than fear.

Perhaps that was his greatest legacy. He showed that thinking is not a theoretical exercise, but a way of living – even when it costs one’s life. And maybe that’s why we still talk about him: because he reminds us that truth requires courage, and that questions, when asked seriously, never remain without consequence.

Weiter lesen

Plato and Aristotle – From the Horizon of Ideas to the World of Experience

After the death of Socrates, much remained unresolved. His students were shaken, not only by the loss of their teacher, but by what his death meant. They had seen that thinking has consequences – that truth is no harmless game. One of them, Plato, would turn that experience into something lasting.

Plato had been a student of Socrates, and you can feel it in every early text. In his dialogues, Socrates still speaks, as if alive. Yet between the questions of his teacher, a new way of thinking begins to form. Socrates had searched without ever holding on to anything. Plato wanted to understand why truth exists at all – and whether it can be grasped without destroying it.

Around 387 BCE, he founded the Academy in Athens – the first place where philosophy truly had a home.

No marketplace, no temple, but a garden outside the city, in the sacred grove of Akademos – a space for language, reflection, and perhaps for the first time, systematic learning. Here, questioning was practiced, not preaching.

While Socrates urged people to reflect on their own lives, Plato sought to bring order to that reflection. He imagined that behind everything visible lay an invisible world – the world of Ideas. What we see, he said, are only shadows of that higher reality. Beauty, justice, truth are not human inventions but timeless forms we can sense but never fully possess.

(A small personal note: my first real philosophy book was by Plato – the “Politeia,” often translated as The Republic. I first encountered it as an audiobook on YouTube – in full reading. (the german version has a better narrator i think) It’s striking how alive those ancient dialogues sound when you listen to them instead of reading – as if Socrates and his friends were still sitting together, arguing about justice.)

Reading Plato, you sense how high he lifted his gaze. He wanted to look beyond the world – toward the eternal forms, toward what endures. But no student remains forever in the shadow of his teacher, and so came Aristotle – the one who brought thought back to the ground.

Aristotle – Thinking as Observation and Method

He too had been a student of Plato, yet he thought differently – more precisely, more soberly, perhaps also more impatiently.

Where Plato sought the ideal, Aristotle sought the real. He cared less about what lay behind things than about how things work. He was the first to observe systematically, to collect, to compare, to classify. Where Plato drew the horizon of ideas, Aristotle laid the foundations of logic, biology, ethics, politics, and rhetoric. He wanted not merely to understand the world, but to describe it – as it is.

In this, something decisive appears: philosophy turns away from speculation and becomes method.

The search for truth becomes the search for justification. Aristotle believed that knowledge does not lie beyond the world but within it. Thought, he said, begins with wonder – and ends only when we understand what we see.

Later he founded his own school, the Lyceum, named after a nearby temple of Apollo. There he taught while walking with his students through its colonnades – hence the term Peripatetics, “the walking ones.” It sounds almost casual, yet it marked the beginning of what we now call science: observing, testing, organizing – thinking as movement between experience and concept.

If Plato asked what the good itself is, Aristotle asked what a good life looks like in practice.

He brought ethics and logic, nature and politics into one system – a framework that still underlies much of modern thought.

One might say: Socrates taught us to ask; Plato, to think grandly; Aristotle, to look closely.

Philosophy Becomes an Art of Living

After Aristotle came a time when thinking had to find a new direction. The political and cultural certainties of the classical age had vanished. Athens, once the center of the world, was now just one city among many. Philosophy lost its solid ground – and found something else instead: the human being as the place of orientation.

New schools emerged – not abstract systems, but ways of life: the Stoics, the Epicureans, and the Skeptics. All three asked the same question, each in a different way: How can one remain calm in an uncertain world?

The Stoics – with Zeno, Seneca, later Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius – sought strength in reason. They believed that we cannot control the world, but we can control our attitude toward it. The Stoic does not aim to be untouched, but unshakable – in harmony with nature and his duty.

The Epicureans, by contrast, saw happiness in moderation. Not wealth, not power, but the quiet, unspectacular life was their ideal. They did not seek suffering, but neither did they chase ecstasy. Epicurus said that whoever wants to learn to live must first learn not to fear death.

And then there were the Skeptics – the most radical of them all. They saw how countless systems and truths stood side by side, and decided to claim nothing final. Their goal was not despair, but peace of mind – the Greek ataraxia, freedom from inner disturbance.

In this age, thinking became personal again. It left the great academies and returned to the streets, the houses, the silence. Philosophy turned into an art of living – not a doctrine to be believed, but a practice to be exercised.

(And before this text turns into a book, we should probably stop here. There will surely be more articles to come – each exploring a different aspect of this vast field.)

So what remains of this little journey?

Perhaps the sense that thinking does not begin with knowledge, but with wonder. That every era, every name, every school is merely a response to the same unease: the wish to understand the world – and ourselves within it.

From the water of Thales to the calm of Epictetus runs an invisible thread: the attempt to find a stance that endures amid change.

Maybe that is the real meaning of philosophy: it shows us that we are never finished – but that questioning itself already brings a measure of clarity. And when, somewhere between everyday life and eternity, you pause for a moment and truly think, you stand, no matter the century, once again beside Thales, Socrates, or Seneca – only with a cup of coffee in your hand.

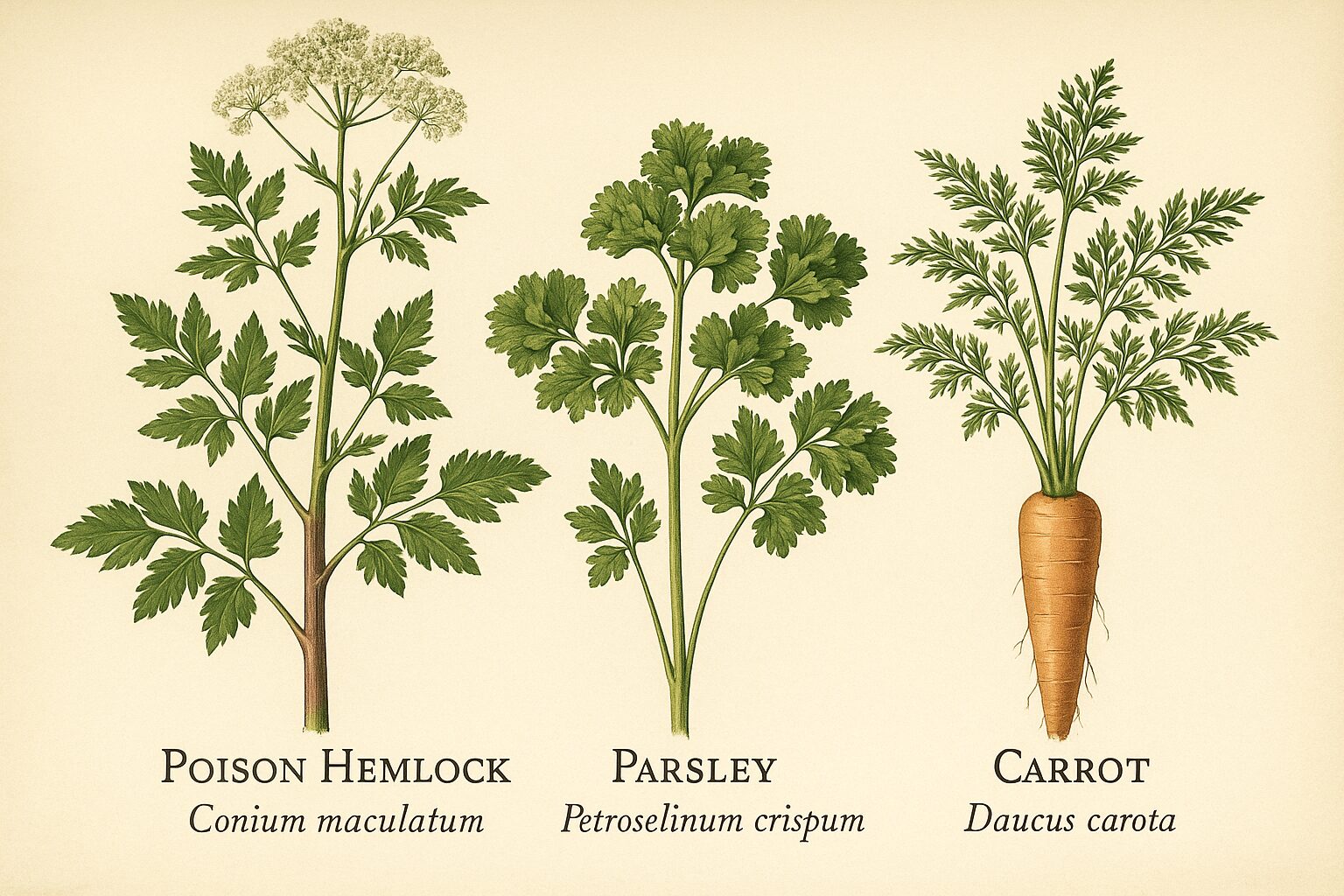

📦 Info Box: The Poison of Socrates

The spotted hemlock (Conium maculatum) belongs to the parsley family and at first glance looks harmless – like parsley or cow parsley in the meadow. Its poison, coniine, blocks the transmission of nerve signals to the muscles. The body gradually becomes paralyzed while consciousness remains clear. At Socrates’ execution, a drink made from this plant was prepared. The paralysis slowly rose from the legs upward until breathing ceased. It was not a painful death, but a quiet, conscious farewell – almost like a final thought detaching itself from the body. Botanically, hemlock is closely related to parsley, celery, and carrot – a strange kinship of healing and poison. Philosophically, it still stands for the boundary between knowledge and experience, between thought and life.